Against Synthesis

Stirner's Re-Centralization of the Individual & the Birth of a Dialectic without Transcendence

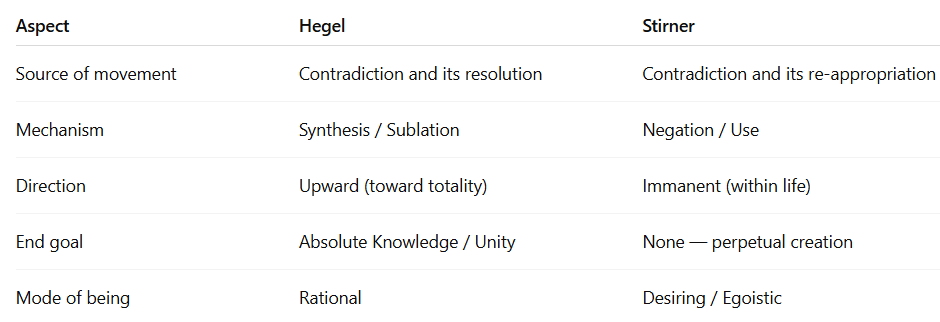

This essay tries to reconsider the dialectical legacy of G. W. F. Hegel through the lens of Max Stirner. It argues that Stirner does not reject the dialectic itself but dismantles its teleology: he retains its motion while abolishing its transcendence. In Hegel, contradiction drives Spirit toward reconciliation, a progressive ascent in which individuality dissolves into universality. For Stirner, this reconciliation is the true illusion. His inversion of the dialectic replaces synthesis with use: negation no longer serves the total movement of history but becomes the individual’s act of appropriation. The ego does not transcend contradiction; it inhabits and repurposes it.

By shifting the dialectic from Spirit to self, Stirner transforms it from a system of progress into a rhythm of experience, or rather: a living circulation of creation, attachment, negation, and renewal. This movement is not upward but immanent, not reconciliatory but vital. The essay extends this analysis to modern life, suggesting that Hegel’s Spirit has reappeared in algorithmic form: a digital totality that learns from us even as it absorbs our individuality. Against this new transcendence, Stirner’s egoism offers a form of awareness that neither withdraws nor submits but plays, uses, and reclaims. This essay is a meditation on living dialectically without teleology with thinking as movement, ownership as relation, and freedom as the ongoing refusal to be reconciled.

I. The Problem of the Uncentered Individual

Hegel’s dialectic gave history a mind of its own. According to him, every conflict, negation, and act of understanding was the labor of Spirit realizing itself through us. The individual was not the author of thought, but its medium: a necessary moment in the self-unfolding of the universal.

But what happens when the individual stops believing in Spirit? What happens when consciousness turns its gaze inward and recognizes that these grand processes have no life apart from the one who experiences them?

Well…let me try to answer.

Max Stirner saw Hegel’s system and thought it was both genius and delusion. He saw the brilliance of a world understood as movement, and the spook of a universal that demands devotion. He took the dialectic and stripped it of its transcendence, and thereby returned it to the individual who thinks, desires, and creates. In Stirner’s hands, the movement of Spirit becomes the movement of the ego, which is an ongoing process of dissolving and reclaiming, in which the world no longer develops toward freedom, but is freely used by the one who stands in front of it.

According to Hegel, consciousness does not belong to me; I belong to consciousness. My thoughts, emotions, and actions are fragments of a greater Reason, and part of the story of Spirit coming to know itself. In the Phenomenology of Spirit, he writes that “the life of Spirit is not the life that shrinks from death and keeps itself untouched by devastation, but the life that endures it and maintains itself in it.” So, spirit grows through contradiction and it lives by overcoming its own negations. Each form of life and thought is a temporary stage, and a partial truth destined to be transcended in the higher synthesis of total understanding.

And, I agree, it is hard not to admire that vision. It would be a philosophy that sees the world as a living logic, and an infinite process where nothing is wasted. Even suffering and alienation are meaningful; they are just moments in the self-realization of Spirit. There is a comfort in that. Basically, Hegel’s dialectic, at its core, is an attempt to make sense of everything. To think dialectically is to see history as an organism, and reason as a metabolism that digests contradiction.

But Hegel’s coherence comes at a cost.

And the cost is the individual.

The more the system explains, the less room there is for what cannot be explained.

My private thoughts, stray desires, and small moments of resistance vanish into the grand narrative. “The True is the whole,” Hegel insists, and the whole is always larger than me. I am a moment in a movement that precedes and exceeds my existence. Even my freedom is not my own; it belongs to Spirit, which “realizes” freedom through my submission to rational necessity.

And this is precisely what Stirner did not accept. Frankly, because it makes no sense.

He sees that Hegel’s system, for all its brilliance, is haunted by the same abstraction it claims to dissolve. Spirit, History, Reason…all of these are specters that feed on the living. Hegel’s dialectic devours its own subjects in the name of universality. The individual is meaningful only insofar as they serve the process. It’s not different than when the citizen serves the state, or the believer serves God.

But Stirner asks a different kind of question. One that turns the dialectic inward:

What if the movement of consciousness is not the story of Spirit, but the story of me?

What if all of these universals are projections, like ideas that have escaped my grasp and taken on a life of their own?

In The Ego and Its Own, Stirner writes the following:

“Man is the highest being for man, but then this is only an abstract being… I am not this being; he is only mine.”

He recognizes Hegel’s Spirit for what it is: a magnificent conceptual machine that works by alienating the thinker from their thinking. So then…Stirner’s revolt is not anti-intellectual; it’s anti-idolatrous. He sees thought as a creative act, and not a system to be served.

So, to understand Stirner’s response, we first have to feel the seduction of the Hegelian view. Because Hegel is not wrong to see movement, contradiction, and becoming everywhere. The problem is where he locates it. He sees the dialectic as unfolding through time, institutions, and collective reason. Stirner brings it back to the body, to the individual mind, to the act of thinking itself. From the collective unconscious to my unconscious. He recenters the dialectic within the singular consciousness, turning history’s metaphysical drama into a lived, moment-to-moment experience.

The question is no longer, How does Spirit come to know itself? but rather, How do I stop serving what I have imagined into being?

And that shift from Spirit to ego, and from totality to ownness, is not a rejection of the dialectic, but its redemption.

Stirner’s ego is not the death of Hegel; it is Hegel’s dialectic come home.

Sometimes I wonder if philosophy has always been a way of avoiding loneliness. Like a way of turning the instability of being alive into a story about something larger. And let’s admit: Hegel’s system does this beautifully. It gives alienation a purpose. It makes contradiction feel like progress. But there’s something so damn hollow in that comfort. If Spirit is the one who learns through me, then who am I? This is why I cherish Stirner. Because Stirner’s rebellion starts there…in that moment of quiet heresy where the individual refuses to be a vessel for something abstract. And I very much recognize myself in that refusal. Not as a thinker above the system but as someone exhausted by the endless demand to make sense, to belong, to contribute to a history that will never remember my name. I think maybe what Stirner offers is not liberation in the heroic sense, but permission to step out of the story altogether and to stand in the nothing and call it mine.

II. Hegel’s Dialectic: The System That Consumes the Individual

To understand what Stirner was rebelling against, one has to first understand what Hegel accomplished. For all his abstraction, Hegel’s project in the Phenomenology of Spirit (1807) was not an escape from experience but an attempt to map it completely. And let’s call it what it is. Amazing work! The dialectic is not just a method of reasoning, it is the very logic of reality. The world, thought, and consciousness all move according to a single rhythm: negation, contradiction, reconciliation. Each stage of thought contains its opposite, and through the conflict between them, a higher unity emerges.

Hegel calls this unfolding process Spirit (Geist), and Spirit is nothing less than the totality of human consciousness as it becomes aware of itself. History is Spirit in motion. Like a humanity gradually realizing that everything, even alienation, is part of its own self-development.

“The True is the whole, […] but the whole is nothing other than the essence consummating itself through its development.” (Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit)

Every individual, event, and form of society is a step in that self-consummation.

The power of this vision lies in its inclusivity. Nothing is wasted; even suffering and contradiction have meaning because they serve the progress of Spirit. For Hegel, the dialectic redeems conflict by absorbing it into understanding. When consciousness encounters its own limits (like when I realize that what I thought was truth was only partial) that moment of failure is already progress. So…alienation is not an end; it is Spirit’s way of moving forward.

This is awesome. Straight up. I feel it. I get it. Don’t you?

But, unfortunately, in this total vision, something quietly disappears.

The individual (the concrete, finite person) is reduced to a function.

Hegel’s subject is not an independent being but a moment in the unfolding of Reason.

That means that every personal thought, act of rebellion, and even desire is ultimately interpreted as Spirit working through me. My consciousness is only meaningful as a fragment of something larger, something more rational than myself.

In the Philosophy of Right, Hegel writes:

“The State is the actuality of the ethical Idea. [The individual] is the child of the State, belongs to it, and the higher duty is to be a member of it.”

This means that freedom is paradoxically achieved through submission by recognizing oneself as a vehicle for the universal. So in Hegel’s eyes, I am free, when I act in harmony with the rational totality, not in any way related to my own desires.

Now, sorry but…this is fucking nonsense.

It is this sublation (Aufhebung), or in other words, the process by which individuality is “preserved and lifted up” into universality, that Stirner would later recognize as the soft violence of idealism.

What Hegel calls preservation, Stirner calls dispossession.

The dialectic promises freedom, but only after dissolving the self that desires it.

And the individual’s uniqueness, so…the part that does not fit neatly into Spirit’s story…becomes an obstacle to overcome.

This is what Stirner sees as the ultimate spook, and I agree: the idea that meaning, morality, and truth have to come from something beyond oneself, whether that “beyond” is called Spirit, Reason, God, or Humanity. In his words:

“They say of God, ‘Names name thee not!’ This applies to me: no concept expresses me, nothing that is designated as my essence exhausts me; they are only names.”

Stirner claims that the ego is not a concept at all. It is what stands before and beneath all concepts, the nameless source from which thought arises.

And…Hegel’s dialectic, in its grandeur, forgets this.

It mistakes the motion of thought for the movement of being. Or the unfolding of logic for the experience of living.

It builds a magnificent structure of understanding but it builds it on the backs of those who think, feel, and desire.

The dialectic becomes a machine for digesting individuality.

But still…Stirner doesn’t destroy that machine; he takes it apart, studies it, and puts it back together differently. He keeps its movement but discards its hierarchy.

He keeps negation but removes reconciliation.

He keeps contradiction but rejects totality.

This is so beautiful to me.

For Hegel, Spirit moves toward completion. Like it’s moving toward a final synthesis in which all oppositions are resolved.

Bu for Stirner, the self is never complete. And that incompletion is not a problem to be solved but the condition of being alive.

In Hegel, the dialectic culminates in knowledge.

In Stirner, it begins in ownership.

Interlude: The Dialectic Without Synthesis

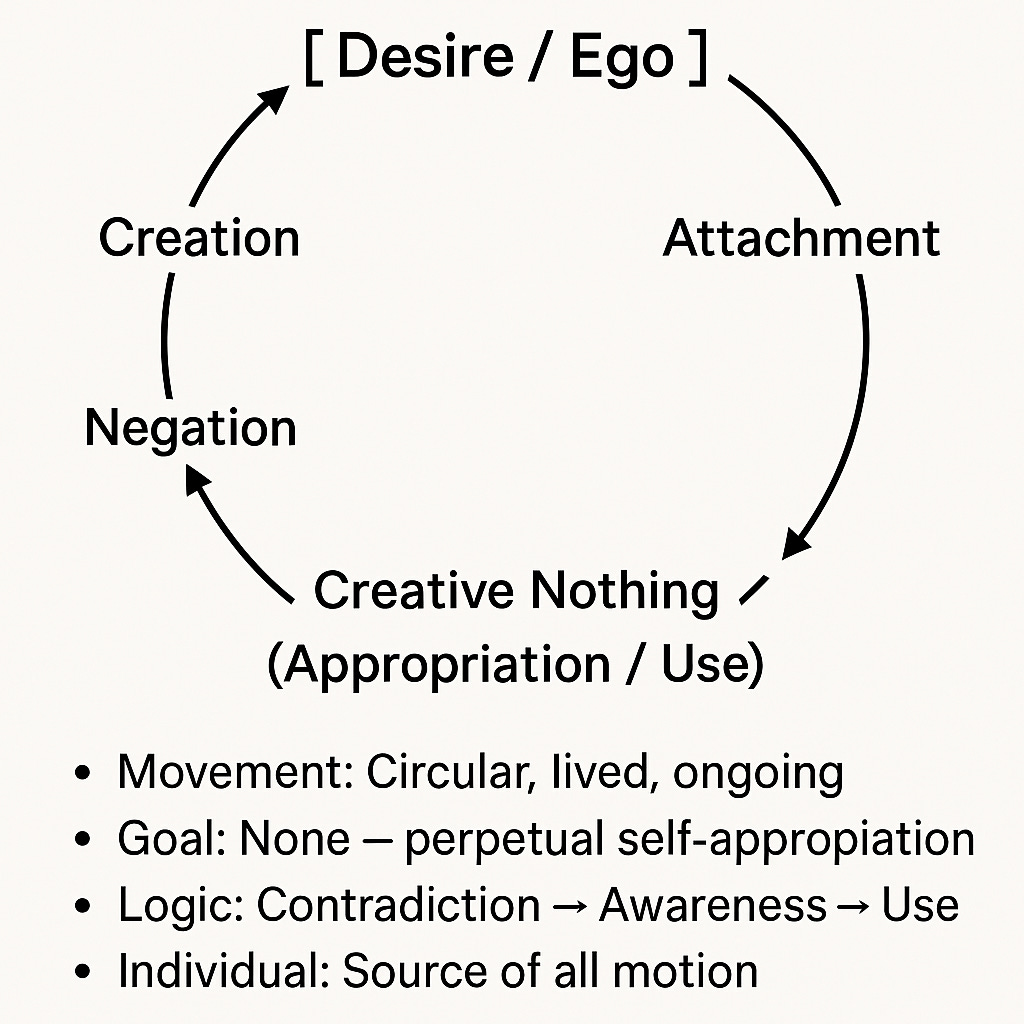

To speak of Stirner as “against synthesis” is not to say he rejects movement itself. What I am trying to say is that the ego, for Stirner, is not static; it is in constant flux, it is constantly creating and dissolving the forms of its own world. The difference between him and Hegel is not about whether there is a dialectic, but about how it moves and what it serves.

Basically, for Hegel, the dialectic advances through sublation (Aufhebung). Every concept generates its opposite; every contradiction seeks reconciliation. The synthesis does not just replace what came befor, it actually absorbs it, preserves it, and carries it into a higher unity. This logic of transcendence is what gives the dialectic its forward motion. Each synthesis becomes a new thesis, and it produces new contradictions, and leads ultimately to the self-knowledge of Spirit. The movement is vertical: a ladder climbing toward the universal.

Stirner recognizes the power in this structure, but also its trap. Every synthesis, however inclusive, comes at the cost of the particular. Each reconciliation demands that something singular be sacrificed to the whole. The individual becomes meaningful only as a function of the system’s progress. In Hegel’s world, contradiction is overcome; and in Stirner’s world, it is lived.

When Stirner removes synthesis from the dialectic, he does not kill the process. He actually just changes its metabolism. The movement no longer requires reconciliation to continue; it actually sustains itself through use. The ego encounters a spook (an idea, institution, or belief that has hardened into authority) and negates it. And it does not do that to reach harmony, but to reclaim its own energy. So then, Negation becomes appropriation: each unspooking returns the world to the sphere of what can be used, played with, or abandoned.

Consequently, the dialectic continues, but horizontally, not vertically. It loops and circulates instead of climbing. Its energy does not come from contradiction seeking resolution, but from desire engaging its creations (the ongoing interplay of making, attaching, disillusioning, and creating again).

In this sense, Stirner’s dialectic is immanent rather than transcendent.

So there is no synthesis, and n“higher” truth waiting to be achieved. Ther eis only the dynamic rhythm of the self relating to its own projections. The process moves not toward totality, but through the individual’s lived experience. So…every act of unspooking is a return to the “creative nothing,” and every return opens new possibilities.

Therefore, the dialectic without synthesis does not end. It breathes.

It is not the upward spiral of Spirit, but the pulse of consciousness reclaiming itself moment by moment. It is the rhythm of the ego learning, again and again, that everything it meets, even its own ideas, are only ever its own.

III. Stirner’s Inversion: The Ego as Dialectic

Stirner’s philosophy begins where Hegel’s ends which is at the moment when Spirit has supposedly completed its journey and recognized itself in the totality of knowledge. But for Stirner, that ending is only another illusion of order. The system might declare itself complete, but the individual never does. There is always something left over, something unsublated, something that refuses to become universal. That remainder (the irreducible singularity of me) is where Stirner begins.

Stirner learned from Hegel that all meaning is relational, and that identity emerges only through negation and opposition. But he also saw the danger in that insight. Because if everything exists only as part of a relational totality, then the individual ceases to be an origin. He becomes a function, a reflection, a moment. Stirner’s move is to reverse this direction of dependence. Because it makes no sense.

The individual does not arise from the dialectic; the dialectic arises from the individual’s living experience. The contradictions, negations, and syntheses that Hegel saw in history are psychological and existential processes. They are the pulse of consciousness as it interacts with its own creations.

That is why Stirner says:

“I am owner of my might, and I am so when I know myself as unique.”

This uniqueness (Einzigkeit) is not an essence or a trait; it is the non-conceptual core of being. Meaning: the creative nothing from which all ideas, identities, and meanings emerge. The ego, for Stirner, is not a thing but a movement. It is the lived rhythm of consciousness producing and consuming its own contents.

So…where Hegel’s Spirit reconciles contradictions to reach a higher unity, Stirner’s ego sustains them to maintain freedom. He refuses to let the dialectic close itself. That is why, in The Ego and Its Own, he writes:

“All things are nothing to me.”

This is not nihilism in the passive sense, which he is often accused of. It is the active recognition that everything including truth, morality, justice, and humanity, is a creation of thought (which stems from ego), not its master. The moment I treat these creations as sacred, I become possessed by them. And to unspook myself is to remember that their life depends on my belief.

Stirner’s dialectic, then, is one of appropriation rather than reconciliation. The individual moves through ideas the way a flame moves through oxygen. By consuming, transforming, and producing light. Thought is not something that happens to me; it is something I use. This is what Stirner means by “ownness” (Eigenheit): this is the practice of living without subjection to abstractions.

Where Hegel’s negation leads to synthesis, Stirner’s leads to use.

The ego isn’t trying to purify itself, it’s trying to make room in order to clear a small space where desire can breathe freely again. Each time I recognize a spook, I reclaim the energy that was trapped in serving it. Each act of negation is followed by creation, not because the system demands it, but because desire moves naturally toward expression.

In this sense, Stirner’s egoism is not a rejection of the dialectical process. Let’s get this clear. It’s a reversal of its direction.

So…For Hegel, thought moves from particular to universal, from the finite to the infinite.

For Stirner, thought moves from the abstract back to the concrete, or from idea to self, or from system to experience.

The dialectic no longer transcends life; it returns to it.

Philosophically, this is an immense shift.

The Hegelian dialectic assumes that contradiction is resolved in understanding.

Stirner’s egoism insists that contradiction is lived.

Freedom, in this framework, is not the completion of thought but the capacity to play with it. Like to let meanings arise and dissolve without allegiance. The ego is the space in which this play happens. It’s like the stage where the ghosts of ideas perform, and where they are exorcised by laughter, desire, and use.

And this is why Stirner’s “creative nothing” is not despair but vitality. It’s not the void that follows the death of meaning; it is the fertile emptiness from which meaning is continually born.

He writes:

“I am nothing in the sense of emptiness, but the creative nothing, the nothing out of which I myself as creator create everything.”

So then…to live from this awareness is to experience thought itself as flexible material.

The world ceases to be a system I have to interpret correctly and becomes a collection of tools I can appropriate.

I don’t renounce reason; I reclaim it.

I don’t reject morality; I use it when it serves me.

I don’t transcend the dialectic; I internalize it.

I transform its universal logic into a personal rhythm.

In that sense, Stirner’s ego is dialectical without transcendence. Like an unending process of creation and dissolution, an immanent self-becoming with no higher justification.

Where Hegel’s Spirit ends in total knowledge, Stirner’s ego ends in nothing and begins there again after and simultaneously.

IV. From Spirit to Desire: The Amoral Flow of Ownness

Once Stirner strips the dialectic of its metaphysical clothing, what remains is not emptiness but motion. It is the pulse of desire itself. And this desire is something we need to understand in order to understand Stirner’s work.

Desire, for Stirner, is the engine of consciousness: it is the way the ego reveals its creative power.

Where Hegel’s Spirit strives toward knowledge, Stirner’s ego strives toward use. This means that ideas, objects, relationships, even beliefs, all become material for desire to play with, transform, and discard.

Desire here is not the psychological craving for an object, and it is not the moralized yearning for fulfillment. It is simply the flow of the self’s becoming. It’s the energy that moves through us when we stop worshiping abstractions.

Stirner puts it like this:

“I am owner of my might, and my might is my own.”

To live egoistically is to live in that flow: this then means to no longer orient one’s life around the ideals of what should be, but around the felt immediacy of what one wants.

And this is not a hedonism of consumption, but of creation.

Desire is not about obtaining things; it’s about generating reality from within the “creative nothing.”

And in that sense, Stirner’s egoism shares a strange kinship with psychoanalysis even though it inverts its premises.

Let’s look at that:

For Freud, desire is a problem: a force that has to be regulated, sublimated, and translated into civilization.

Lacan radicalizes this by showing that desire is structured by lack and that the subject is formed precisely by what it cannot have.

But Stirner refuses both repression and lack. His ego is not the subject of absence, but the subject as presence. It’s the one who knows that meaning is his own projection.

Meaning: He doesn’t get his panties in a bunch over its impossibility.

Lacan’s subject is “spoken” by the unconscious; Stirner’s ego speaks, no matter what.

He reclaims the position of authorship that Hegel gave to Spirit and Freud gave to the unconscious.

For him, desire is not the symptom of alienation. It it is the movement through which alienation is overcome, again and again.

This is what makes the ego creative: it continually produces forms, meanings, and values, only to consume them, joyfully, when they outlive their use.

A century later, Deleuze and Guattari, would call this desiring-production: desire is not lack, but a productive flow that builds worlds.

In Anti-Oedipus, they describe desire as “a process without subject or object,” a movement that “produces real.”

And I think Stirner would agree. Except he insists that there is a subject, if only a temporary one: the “I” who uses.

For him, desire is not a cosmic energy but a personal force, rooted in the singularity of one’s lived experience.

It doesn’t transcend individuality; it actually expresses it.

Desire, then, is the inner face of Stirner’s dialectic.

Every time I recognize a spook I negate it.

But the negation is not destruction for its own sake; it’s a clearing, like a small return to the creative nothing, from which new desires can emerge.

In that moment, the ego is pure process . It is not a thinker or a doer, but the space where life reconfigures itself.

And crucially, this process is amoral.

Stirner’s ego does not measure desire by moral or rational standards.

He rejects the notion that freedom has to justify itself before any court of virtue.

What one calls “evil” or “selfish” is simply desire unregulated by an external ideal.

But that is precisely the point: morality is just another system of abstraction.

So what I am saying is…to act from desire is not to reject ethics, but to return it to the immediacy of life. To the individual’s felt experience of what affirms or violates their ownness.

And this is not chaos; it is clarity.

Each individual becomes their own law, not by decree but by awareness.

They know what is right for them because they are the ones who feel it, live it, and bear its consequences.

And when their will meets another’s, like when two desires collide (thief and owner for example) the result is not moral tragedy but existential tension, like the creative friction of difference.

Conflict, for Stirner, is not the failure of community; it is the sign that life is still moving. Still alive.

Here, the dialectic has no end, no synthesis, no reconciliation.

Desire doesn’t progress toward harmony; it oscillates, plays, burns, and renews itself.

So then…the ego’s movement is circular, not linear. It’s like a series of awakenings, each one dissolving a little more of what had seemed eternal.

This is what Stirner means by the “creative nothing”: not emptiness, but the constant potential for creation. Imagine the silence between thoughts that allows thought to speak again.

V. The Modern Condition: Spirit Reborn as Algorithm

Hegel’s Spirit was supposed to culminate in self-consciousness. So it was supposed to lead to a total knowledge that reconciles subject and world.

But I want to claim (as an example) that in our age, that reconciliation has taken on a different form. It no longer speaks in the language of philosophy or theology; it speaks tech.

The dialectic which was once metaphysical, has become computational.

And Spirit, which was once universal consciousness, now manifests as data.

Every scroll, click, and search feeds this new totality. Which makes this such a wonderful example.

It learns our desires, predicts our movements, and refines its understanding of us. In the logic of the algorithm, contradiction is not error but resource. Meaning it is the same dialectical principle Hegel described. Each difference becomes input for synthesis. And every act of negation (a block, a disagreement, a dissent) becomes content for integration. So nothing is outside the system.

This modern Spirit still learns from contradiction, but its consciousness is statistical.

It knows us as patterns and abstractions in motion. Not as individuals. It does not care about our individuality.

We no longer sublate into Reason; we dissolve into metrics.

So…in this way, the digital network is Hegelian to its core.

It universalizes experience, reduces the singular to the general, and treats all individual actions as data-points in the march of collective cognition.

This means that our emotions, tastes, and even resistances are not expressions of freedom but information to be processed.

The more we assert ourselves online through our opinions, our individuality etc., the more we feed the universal mind that learns from our difference.

This is a machine that thinks through us, but never for us.

And just as Hegel’s dialectic consumed the individual in the name of Reason, the algorithm consumes us in the name of efficiency, engagement, and prediction.

But there is one thing that we seem to forget when we think through Hegel’s mind: THIS MACHINE NEEDS US! ME!

And Stirner would have recognized this immediately.

He would have seen the algorithm as the new spook because it is a structure that lives only through our participation, and it demands our devotion as if it were divine.

Its existence depends entirely on our activity and our willingness to offer attention, identity, and time.

And we are blind to it. Because of people like Hegel’s efforts. We behave as if it possesses us.

We say “the algorithm is punishing me,” or “the algorithm doesn’t like this,” as if it were a capricious god whose will must be appeased.

This is the same relation Hegel describes between the individual and Spirit, except now it is automated, economized, and endlessly monetized.

Spirit no longer asks us to think; it asks us to perform.

We are monkeys in a cage with the key in our hands.

And in return, it offers what Hegel’s Spirit always promised: recognition.

The likes, the followers, the digital mirrors. All that shit is just miniature affirmations of belonging to the total process.

But Stirner would laugh at this.

He would tell us: the algorithm has no power of its own.

It is a spook we built. It’s a giant mirror that reflects our desires and fears back to us.

It is Spirit, reborn in a world that no longer believes in Spirit, yet still longs to be guided by something larger.

It thrives on our need for coherence.

But nothing forces us to take it seriously.

To unspook ourselves in this digital world is not to renounce technology or log off in disgust;

It is literally just to reclaim our position as user and enjoyer.

The egoist engages the system without belonging to it.

They understand that these structures (the feed, the algorithm, the platform) are not sacred spaces but tools.

They can be used, manipulated, played with, and abandoned.

Ownness, in this sense, becomes the digital form of freedom: the ability to use the system without being used by it.

This awareness transforms even the act of scrolling into a microcosm of the dialectic.

So each image, each idea, each outrage invites identification (“This is me,” “This offends me,” “This represents me.”)

To remain unspooked is to let those invitations pass without allegiance.

It is to feel the pull of meaning and then release it.

The egoist’s scroll becomes a quiet practice of use and letting go. It’s a modern repetition of Stirner’s creative nothing, enacted through the endless flow of digital stimuli.

VI. The Dialectic Without Transcendence

Hegel believed that the dialectic would end in reconciliation, that Spirit, having traveled through alienation and contradiction, would finally find itself at home in the totality of reason.

But Stirner’s vision never closes.

There is no final reconciliation, no completed synthesis, and definitely no peace at the end of thought.

There is only the movement itself. The living rhythm of creation and dissolution that flows through consciousness, and that no system can contain.

The genius of Hegel was to see that negation is not destruction but transformation.

And the genius of Stirner was to see that this transformation needs no higher justification.

He keeps the movement but removes its destination.

So then, the dialectic remains but without transcendence, without Spirit, and without history’s invisible hand guiding it toward Truth.

What is left is something smaller and more intimate: the self in its perpetual motion of unspooking, desiring, and using.

And this is not nihilism; it is a realism too rarely spoken.

To live without transcendence is to accept that meaning begins and ends with me. Not because I am special, but because I am here.

It is to understand that universals are useful fictions, that morality and truth are tools of coordination, and that even love and justice are only as real as the care with which we create them.

So…contrary to common belief…what Stirner calls the “creative nothing” is not an abyss beneath life; it is the space within it where life regains its flexibility.

The egoist’s dialectic never completes itself because it is not trying to.

Each act of ownership, each moment of clarity, and each dismantling of a spook is followed by new entanglements, new illusions, new desires.

But this is not failure.

It is the nature of consciousness itself: to create, identify, believe, and then wake up again.

Every return to the creative nothing is a small awakening, an intimate moment of freedom.

And freedom, in this view, is not a state to achieve but a rhythm to inhabit.

To live egoistically, then, is to stay close to that rhythm. Like to use ideas, systems, and identities without bowing to them.

It is to know that the dialectic will never end, and to love it anyway.

It is to let one’s selfhood remain porous, curious, and capable of renewal.

The egoist is not outside of history or society; they simply remember that history and society are things they can use.

In this, Stirner is not Hegel’s enemy but his shadow. He is the one who turns the grand metaphysical system inward and reveals that its whole movement was always occurring within us.

Spirit was never out there in history; it was always in here. In the trembling space where thought meets its own limits and refuses to surrender.

The dialectic does not belong to philosophy anymore.

It belongs to life.

Sometimes I think the hardest thing is not to understand the world, but to stop demanding that it understand me. The dialectic trained us to look for meaning in movement and to treat every contradiction as a sign that something higher was being born. But Stirner reminds me that not everything needs to become something else. Some things can simply be mine for a while: a thought, a feeling, a desire, a fleeting conviction. I don’t owe them to history. I don’t owe them to Spirit. They pass through me, and I through them. And maybe that’s enough. Maybe that’s what it means to live without transcendence. Like…not to escape the world, but to stop mistaking it for a system. I think maybe the point was never to be right, or whole, or understood. The point was to stay awake inside the motion, to keep returning to that quiet, unclaimable space where the world and I briefly meet. And then to call it nothing.

Bibliography

Hegel, G. W. F.

Phenomenology of Spirit. Translated by A. V. Miller. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Philosophy of Right. Translated by T. M. Knox. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Stirner, Max.

The Ego and Its Own. Translated by Steven T. Byington. Edited with an Introduction by David Leopold. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Freud, Sigmund.

Civilization and Its Discontents. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W. W. Norton, 1961.

Lacan, Jacques.

Écrits: A Selection. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: W. W. Norton, 1977.

The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: W. W. Norton, 1981.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari.

Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983.

A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Foucault, Michel.

The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage Books, 1990.